We can’t reform our nonprofit news organizations if we’re broke.

What Erika Owens gets wrong in her “socialist” proposal.

by Jason Pramas

As a longtime journalist, a longtime nonprofit news publisher, and a longtime socialist, I was immediately intrigued by the title of Erika Owens’ recent think-piece: “A socialist approach can work in business: Journalism nonprofit leadership can blend solidarity values and financial sustainability.”

Owens is one of four co-directors of OpenNews, a support network for tech staff working in the news industry. Her piece was penned in conjunction with the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowship she’s been doing at Stanford this year.

Reading the article, I noted that Owens’ political thrust was more what one might call socialist-adjacent than socialist—a modicum of social democratic thinking sprinkled with a light dusting of cultural anarchism over the kind of ideas you’ll hear at any local Democratic Party club before marching orders come down from party leadership to be good children and back another tax break for the rich. Which is fine. I like local Democratic activists and just wish more of them would hold onto their typically egalitarian and “small d” democratic ideas as they move up the ranks of their corporate-dominated party.

But my immediate reaction to Owens’ advice to journalism nonprofits was: Don’t fall into the trap of forgetting all the small news organizations struggling to survive at the local and regional levels.

That’s the type of news outlet that I have run for many years…and the very type of outlet for which a bunch of fellow publishers and I launched the Alliance of Nonprofit News Outlets last August, a grassroots trade association that is 43 member-organizations strong as of this writing.

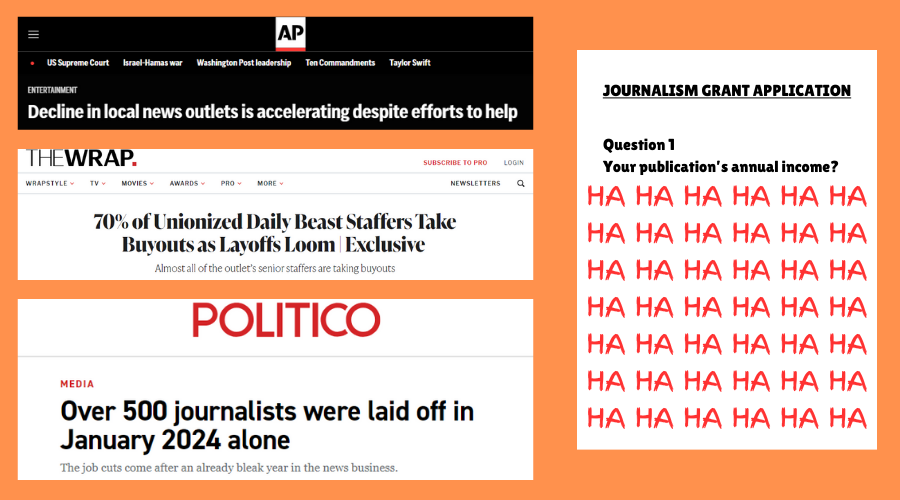

Most outlets in the nonprofit sector of the news industry are quite small by any metric. And the problem that we face is that we have barely enough money to scrape by day-to-day. We are forced to remain outrageously understaffed, woefully underpaid, and unable to offer career paths for the swift-shrinking legion of young people trying to follow in our footsteps.

Indeed, far too many of us run essentially volunteer operations. This is particularly true of those of my colleagues who have been pensioned off or canned from hedge-fund-owned chain publications, as the greed-driven contraction of the news industry accelerates into its terminal phase.

Meaning there is a not-inconsiderable number of experienced journalists who are trying to stop the communities they covered for decades from becoming news deserts but are receiving little or no remuneration for their public service.

So that’s where our sector of the news industry finds itself in this era. Having lost, to cite a relevant example, at least 2,900 local newspapers in the US since 2005 (according to the State of Local News project at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism), hundreds of new, often digital-only, news outlets working alongside surviving legacy operations are trying to hold the line for American journalism at the community level.

And most of us are on our last legs. Even outlets that just launched.

Owens’ prescription for the nonprofit news industry consists of four points:

- “Redistribution: The concept of giving what you can and taking what you need can truly, I promise, be a sound business strategy.

- “Economic justice: We must value workers and have their needs central in budget planning.

- “Centering relationships: Let’s organize around people and our ability to learn from and support one another.

- “Not trying to do it all: Know your role, stick to it, and expand impact through collaboration.”

So far, so good. Running an honest shop, treating your crew as you wish to be treated, striving to function like a stable family, and right-sizing your operation—that all sounds like reasonable business advice to nonprofit publishers.

Yet to journalists like me, on the ground running community news organizations in the service of democracy, what matters is this: Does Owens understand that what we really need, first and foremost, in this disastrous era for our industry is…money?

True, in her article’s first section, Owens mentions redistributing money. But she doesn’t mean drawing down great wealth from the rich and the institutions, like foundations, under their control and redistributing that wealth among (ideally/potentially) helpful organizations like 21st century community news outlets that are perennially broke, the way we talk about doing in ANNO.

Instead, she suggests that money is just sort of sitting out there among the audiences of news organizations. She compares the dire business environment that news outlets face to a potluck and says that everything news groups need is available in their existing networks, if they just leverage it properly.

Her only specific example is this: “[A]t OpenNews, we changed our conference ticket structure to make it easier for some people to pay more, some people to pay less, and some people to not pay at all. And you know what? We brought in a ton more money than when there was just one ticket price. In addition, the overall event budget structure included funds for scholarship payments to participants who needed funds for travel or participation.”

The biggest program that OpenNews runs looks to be an annual conference for what it calls “news nerds,” so it makes sense that Owen’s example of redistribution talks about the benefit of making sure there are cheaper and even comped tickets at such an event. Overall, she indicates that her organization profits by maximizing the number of possible attendees in this fashion over years. Which is, like, cool and everything—albeit a notion long in good event organizers’ playbooks.

But it’s not an example that provides any helpful information to the legions of broke news organizations out there. And sure, that’s not the article’s stated angle, but I think if you’re talking about socialism in the news business, you need to at least talk about how best to float all the proverbial news boats in the capitalist sea in which we all find ourselves.

Pressing forward, Owens’ second section on economic justice starts by saying that “budgets are moral documents.” A noble sentiment to be sure.

She continues by asking: “What is the lowest payscale? Is it meaningfully above minimum wage? … What is the highest a staff member can make at the org? So, for a journalism org, what’s the highest a senior reporter makes? What is the differential between the lowest pay and the top leadership of the organization? These factors and the needs of workers should be central to any planning around budget adjustments, too.”

Then she concludes the section: “Unions are also obviously hugely important in setting the terms for compensation for employees. It’s been great how many negotiations have also covered related topics like limiting the amount of time freelancers/contractors can work before they must be given the opportunity to become a full employee.

“It’s critical that we compensate workers for all of the time they spend doing journalism, including the often invisible and unpaid work that many journalists do, especially people of color and women. This background work of advising, network building, research, and relationship support is what powers reporting and the sustainability of our organizations.”

And here the problems with her first section relative to the crisis in local journalism are compounded.

Unions?! I’m a longtime labor activist, was a member of several union locals, have been a union staffer, and sometimes a unit leader. I’ve negotiated contracts, helped start a union, and even lost a job for my trouble. But most community news organizations, nonprofit or otherwise, barely have any paid staff, making the issue of unionization moot.

Payscale?! This assumes regular pay that goes up year by year … and that there’s some kind of employment ladder. Lowest paid and highest paid workers, junior and senior reporters?! For the lucky outlets that have more than one paid staffer, there will generally be precious little daylight between salaries irrespective of experience.

Support workers?! Most staff at community news organizations have to be our own support workers. (There’s rarely any money to even pay contractors for specialized tasks.)

Giving freelancers ladders to full employment?! Literally a pipe dream at this juncture.

In the third section, Owens talks about basically flattening hierarchies at news organizations—standard advice in some management and human resources circles for at least 30 years.

“Hierarchies and received wisdom determine how many of our workplaces are constructed,” she says. “Ideas of leadership often conjure an image of a single person. This simplistic idea of leadership driven by one person alone is another capitalistic narrative of scarcity and exceptionalism that infects many workplaces, but there are other options.

“I’ve been experimenting with different modes of shared leadership, and have become really interested in scholarship around ‘relational leadership,’ the idea that leadership is something that we ALL enact, together. Why not construct our organizations in a way that serves the needs of the entire staff? With back to the office mandates, we hear so much about the importance of informal discussions. That’s relationship building time! But it doesn’t have to just happen around a virtual or physical water cooler, it can be infused into how meetings are conducted, who makes decisions and how, into the structure and plan for the entire organization.”

Again, the clear assumption is that most nonprofit news organizations are large enough to have real hierarchies (leaving aside whether job specialization is really synonymous with hierarchy for the purposes of this critique) … which is simply not the case. Let alone offices. In fact, since the start of the COVID pandemic, more and more outlets in the community news sector have been run from publishers’ homes, mine included—where there are few water coolers to be found.

Owens’ fourth and final section on “staying small” doesn’t improve on the previous three.

“One of the ways I managed to keep OpenNews’ budget going in recent years was by keeping the organization small. Staying small is always an option.

“Chasing grants, chasing growth, chasing new projects, these are not the only ways to keep an organization afloat. Growth is also not the only way for an organization to evolve and flourish. I was really cautious about when to hire new employees and how. When so many people seem to measure success by growing budgets and team sizes, it can feel like it’s not really an option to stay small or that it is a failure somehow. But I don’t think that’s true (even if the imposter syndrome does continue to tug at me). In addition to having a more manageable budget to fundraise for, one of the other benefits of staying small is that it makes it easier to focus on your organization’s specific remit.”

Staying small isn’t an option for most community news organizations; it’s the default state that the current political economy of our industry forces hundreds of us into. The only alternative is to go under—something too many of us have already done and too many news outlets on the ground will be doing in the next few years unless we see serious funding infusions from foundations, corporations, nonprofits, unions, and/or government.

The “pennies from working people” model that sustained American newspapers and magazines in the 19th century is long gone and “the Internet” has clearly not succeeded in providing a steady stream of funding for most entrants through the latter-day version of said pennies—crowdfunding or micropayments or whatever.

In fairness, Owens’ does touch on channeling government money to the news industry—which I, too, support as long as many safeguards are built in to prevent turning reporters into government mouthpieces. She also calls for various players in and around journalism to collaborate more, something we certainly agree with in ANNO.

But all in all, for an article aimed at offering advice to the entire nonprofit sector of the news industry, I think “A socialist approach can work in business” is a swing and a miss.

I appreciate that Owens’ is recognizing that capitalism is generating “deep economic disparity” in the U.S. and is suggesting that there might be more fair and just ways of running an economy, starting at the individual business level.

But, unfortunately, she doesn’t reflect on the utter destruction of the news industry at the community level. Nor does she remark upon the hollowing out of the major news organizations now proceeding apace at the national level. Though she did do a bit of both in a piece posted earlier this year. However, that analysis of current efforts to solve those problems was also over-optimistic (especially on the topic of worker co-ops).

These matters are no longer an academic discussion for most journalists; so it’s imperative that commentators with elite platforms like Owens be willing to take a clear-eyed look at the manifold crises we face if they want to help remediate them. Because there’s no time to lose. We’re watching our industry disintegrate around us. The entire Fourth Estate is under serious threat of extinction. Something our beleaguered democracy—which was never as strong as it could have been—can ill afford. So we need to regroup and rebuild the news industry at speed or our society will suffer the consequences of our failure.

Jason Pramas is the executive director of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism (BINJ), executive director of the Somerville Media Fund, and the founder of the Alliance of Nonprofit News Outlets (ANNO). Read more at the Local News Blues contributors page.